The Russian

Social Contract

Russia has a social contract with its citizens. Is it about to expire?

Additional questions remain: how have public goods in Russia improved so much with very little improvement in state capacity? Can this be sustained through economic challenges stemming from the war in Ukraine and resulting sanctions? Could Putin's "special military operation" put these rising living standards at risk, with consequences for domestic order?

Oil: Russia's Social Elixir?

Rich in oil and natural gas, Russia has utilized its national income to prop up public goods provision. However, while these resources have left Russia nearly free of sovereign debt held abroad, economic development has been limited. While income from the extraction industry keeps Putin's regime in power and Russian citizens tacitly complicit, how might it affect the nation's future?

"You'd expect a country with better state capacity to have better public goods, same with democracy. However, Russia is a very interesting case, because you have really substantially declining democratic accountability, and very stagnant and low state capacity. And yet, public goods provision has gone up over time. And that really relates to what people call this Russian Social Contract, which is that you keep mum about what the government is doing and they will provide you with a reasonable amount of public goods and that, of course, is subsidized by fossil fuel revenues. While it might look possible to have a very weak democracy, and relatively high public goods provision, in the long run, it's difficult to sustain."

– Edward Knudsen, Research Associate, UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs

The Power Vertical

The post-Soviet "color revolutions" that overthrew autocratic regimes in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan in the first decade of the 21st century posed a threat to Russian autocracy. Putin's answer: maintain political stability and political loyalty at any cost.

Vladimir Putin’s latitude to maintain the social contract without restructuring state institutions or improving democratic accountability has led to a likely unsustainable model. His efforts focus on re-nationalization of private firms and an over-regulated state.

The resulting “power vertical” has established an encompassing and centralized hierarchy of control that evaluates political actors, especially regional and municipal authorities, by their production of regime-confirming election results, not by their socio-economic achievements. This system allowed for loyal oligarchs and top bureaucrats to capture state institutions and their assets.

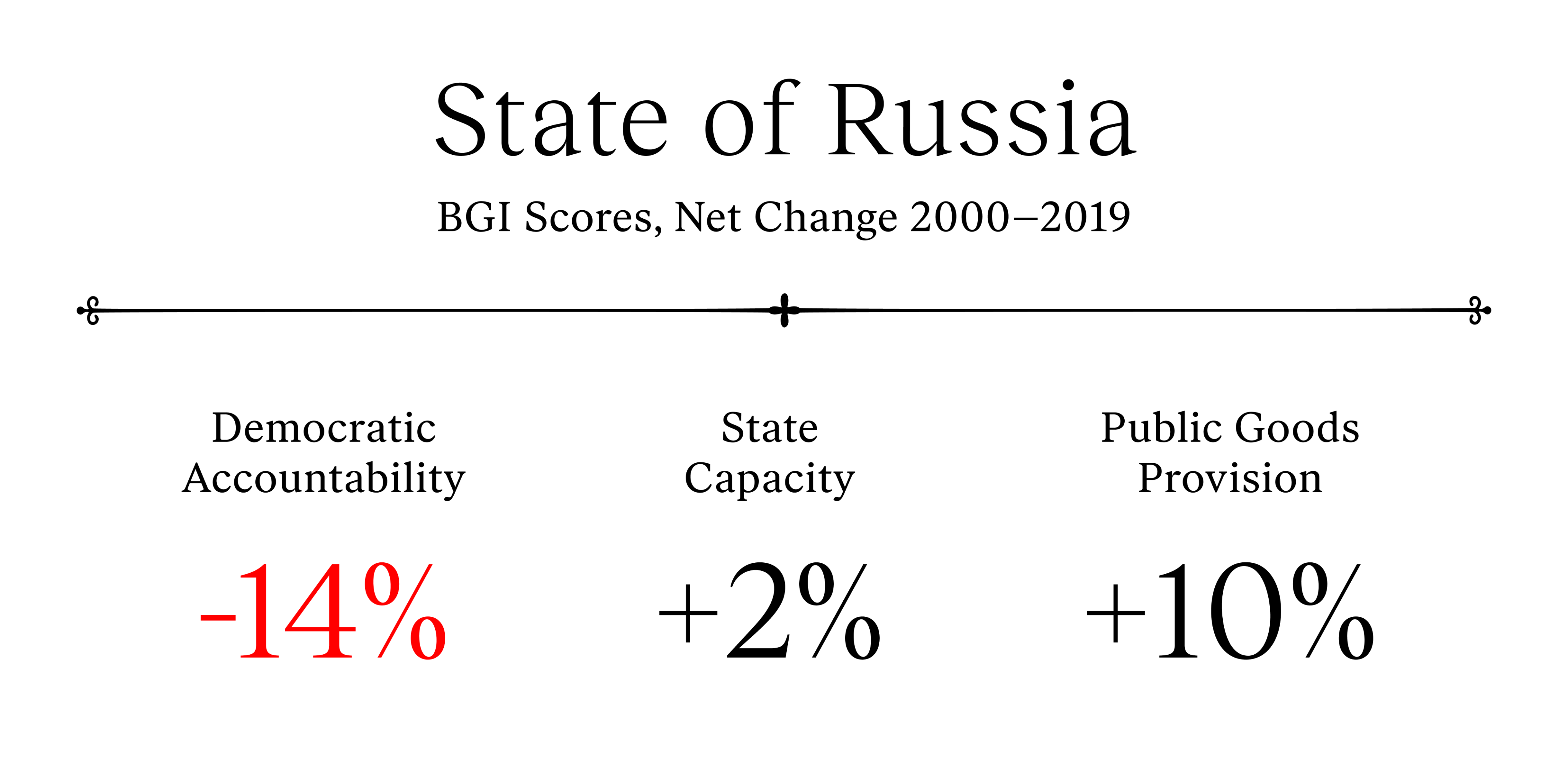

Data from the Berggruen Governance Index sheds light on how a centralized power vertical in an authoritarian framework, under conditions of rent-seeking elites, led to a medium-low state capacity that practically did not change over the course of 20 years. To put this in perspective, state capacity in Russia remains even lower than in other large middle income countries like China, India, and Brazil.

BGI State Capacity Scores for 2019 (out of 100)

China

44

India

49

Brazil

51

Russia

34

Democratic Deterioration

With Russia suffering from a deep economic crisis and the re-centralization of power under Boris Yeltsin, widespread dissatisfaction with democracy left an open door for the Putin regime, which abandoned the democratization begun with Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost political reform in the 1980s. Putin's power vertical served as a death knell to the already dwindling hope for democracy in Russia. His authoritarian modernization project imposed centralized state control over all societal spheres, including the enforced conformity of the judicial process, the co-optation of media and civil society, as well as seizing control of the electoral process and its outcomes.

The data from the Berggruen Governance Index reflects this "authoritarianization" of Russia and shows a clear and rapid drop of the democratic accountability level from 53 in 2000 to 37 in 2019 that is not equaled by most post-Soviet countries.

Post-Soviet Accountability Trends, 2000–2019

Ukraine

+9%

Belarus

+2%

Moldova

+0.5%

Russia

-15%

As a result of these power moves, all three sub-indexes of the BGI's democratic accountability scores reflect the same downward trend in Russia's state-society relations. Judicial oversight is now bound to political will and while some executive officials may raise questions, they do so mostly as part of political shadow games, rendering institutional accountability very weak.

Shifting election rules and widespread electoral fraud have plagued electoral accountability. Most notably, the 2011 legislative election led to the longest mass protest in the country's history. What's more, the electoral infrastructure and the party system are both under government control, systematically discriminating against oppositional candidates and undermining any opportunity for political competition. Since Vladimir Putin became president the first time in 2000, no other party has substantially defied or challenged the dominating state party, United Russia, in parliament or elsewhere.

A Nation Behind Closed Doors

Alongside the decline of institutional and electoral accountability under Putin, the BGI's sub-index for societal accountability also shows a downward slide. Lack of free press further insulates Russia's autocratic institutions.

Media freedom is practically absent, with all TV channels under state control, and all newspapers either co-opted or closed down. The last of the independent media outlets, the oppositional newspaper Novaya Gazeta and the TV channel Dozhd, recently closed down their activities in Russia because of persecution due to regulations concerning reporting on the current “special military operation” in Ukraine. The internet has been the last stronghold for freedom of expression, while the laws on demonstrations and public events have been amended to severely restrict dissent and critique of the state’s status quo.

Public Goods: The Autocratic Keystone

The beginning of Vladimir Putin's first presidency in 2000 coincided with strong global commodity demand, and Russia's export of rich natural resources, such as oil, gas, and precious metals, led domestic income to grow exponentially. In contrast to state withdrawal during the 1990s, which caused a deep economic recession and extreme austerity, the beginning of the new millennium saw the introduction of a certain "retraditionalization" in social welfare provision, with a more expansive statist welfare role under (semi-) authoritarian regime conditions.

This commenced the aforementioned unwritten social contract between the Putin regime and its citizens, who traded growing social security and individual welfare with political loyalty and non-interference.

The increased public goods provision became readily apparent. In particular, the rapid increase of life expectancy at birth (basic medical care indicator) from 65 years in 2000 to 69 years in 2010 and 73 years in 2019 appears to be the strongest indicator for the social public goods delivery sub-index. The graph below illustrates Russia's increase in GDP per capita (constant LCU) as defined by The World Bank, against the increase in life expectancy.

Economic public goods such as food, employment, and healthcare have been delivered consistently throughout the country thanks to a social contract bound to the general resource-based economic upheaval.

Despite slowing economic growth due to the effects of the global financial crisis in 2008 (falling investment and consumption), falling oil prices and sanctions because of the annexation of Crimea in 2014, social public goods delivery kept rising. Social and economic goods delivery indices in BGI continued to grow in 2018-2019 despite a declining economy, thanks to the reintroduction of so-called federal projects that were designed to boost development in areas such as education, health care, public health, ecology, labour productivity and others. However, continuation of public goods delivery on such a high level will be difficult because of growing budget constraints, which already caused a halt or considerable resizing of some federal projects in 2020.

Will the “Social Contract” Expire if Public Goods Delivery Falls?

The social strain of the war in Ukraine, increased Western sanctions, high inflation, and a general lack of support around the globe will challenge Russia's social spending—the basis for the social contract—making it even more difficult to maintain the current high level of public goods provision that is crucial to maintain public support. Despite the relatively good health of the Russian energy sector, most other industries have been hit hard because of Western sanctions against the import of intermediate and high tech goods. The real value of pensions and other social welfare payments are already eroding due to inflation.

Russia’s low level of democratic accountability continuously poses a great problem due to the lack of signals from within society about the actual status of Russia's public legitimacy and of social grievances in the population. During a sustained economic crisis under wartime conditions, the quality of governance can hardly be expected to improve. Even so, decreasing social spending will most likely not push ordinary Russians to the streets, because the previous social contract has been partly replaced by a promise of returning to imperial power and victory over global adversaries. With the anniversary of the beginning of the war in Ukraine coming up on February 24, the world will be watching.

Photo & Illustration Credits (in order of appearance):

Eduardo Barrios ; Sanaea Sanjana; Lucas Carvalho ; Vlad Sargu ; Vladimir Soares ; Remy Gieling ; Jana Shnipelson ; Karen Grigorean ; Kirill Kruglikov ; Egor Myznik ; Regös Környei ; Timon Studler ; Ivan Lapyrin ; Mikhail Volkov ; Kukuh Wachyu Bias ; Elena Babushkina

Produced by the Berggruen Institute, based on findings in the 2022 Berggruen Governmental Index, an ongoing collaboration with UCLA. The 2022 Berggruen Governance Index examines the varied performances of countries with a conceptual framework that incorporates democratic accountability (Quality of Democracy) and state capacity (Quality of Governance) as key factors of public goods provision (Quality of Life). Over the span of 20 years, the Index analyzes 134 countries across 3 main indices and 9 sub-indices to examine the relationship between Quality of Democracy, Quality of Government, and Quality of Life.